Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

What is it?

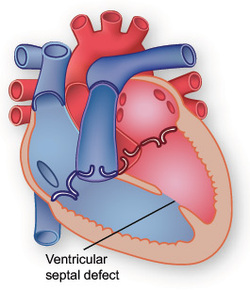

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a defect in the septum between the right and left ventricle. The septum is a wall that separates the heart's left and right sides. Septal defects are sometimes called a "hole" in the heart. It's the most common congenital heart defect in the newborn; it's less common in older children and adults because some VSDs close on their own.

What causes it?

In most people, the cause isn't known but genetic factors may play a role. It's a very common type of heart defect. Some people can have other heart defects along with VSD.

How does it affect the heart?

Normally, the left side of the heart only pumps blood to the body, and the heart's right side only pumps blood to the lungs. When a large opening exists between the ventricles, a large amount of oxygen-rich (red) blood from the heart's left side is forced through the defect into the right side. This blood is pumped back to the lungs, even though it has already been refreshed with oxygen. Unfortunately, this causes the heart to pump more blood. The heart, especially the left atrium and left ventricle, will begin to enlarge from the added work. High blood pressure may occur in the lungs' blood vessels because more blood is there. Over time, this increased pulmonary hypertension may permanently damage the blood vessel walls. When the defect is small, not much blood crosses the defect from the left to the right and there's little effect on the heart and lungs.

Procedures

Surgical treatment for ventricular septal defects involves plugging or patching the abnormal opening between the ventricles. Two approaches are used:

Surgery to close a ventricular septal defect generally has excellent long-term results.

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a defect in the septum between the right and left ventricle. The septum is a wall that separates the heart's left and right sides. Septal defects are sometimes called a "hole" in the heart. It's the most common congenital heart defect in the newborn; it's less common in older children and adults because some VSDs close on their own.

What causes it?

In most people, the cause isn't known but genetic factors may play a role. It's a very common type of heart defect. Some people can have other heart defects along with VSD.

How does it affect the heart?

Normally, the left side of the heart only pumps blood to the body, and the heart's right side only pumps blood to the lungs. When a large opening exists between the ventricles, a large amount of oxygen-rich (red) blood from the heart's left side is forced through the defect into the right side. This blood is pumped back to the lungs, even though it has already been refreshed with oxygen. Unfortunately, this causes the heart to pump more blood. The heart, especially the left atrium and left ventricle, will begin to enlarge from the added work. High blood pressure may occur in the lungs' blood vessels because more blood is there. Over time, this increased pulmonary hypertension may permanently damage the blood vessel walls. When the defect is small, not much blood crosses the defect from the left to the right and there's little effect on the heart and lungs.

Procedures

Surgical treatment for ventricular septal defects involves plugging or patching the abnormal opening between the ventricles. Two approaches are used:

- Surgical repair. This is the procedure of choice in most cases. Surgical repair of a ventricular septal defect usually involves open-heart surgery, which is done under general anesthesia. The surgery requires a heart-lung machine and an incision in the chest. The doctor uses patches or stitches to close the hole.

- Catheter procedure. This method may be used to close some ventricular septal defects. Patching during catheterization doesn't require opening the chest. Rather than opening the chest, the doctor inserts a thin tube (catheter) into a blood vessel in the groin and guides it to the heart. The doctor then uses a small mesh patch or plug to close the hole.

- Hybrid procedure. A hybrid procedure uses surgical and catheter-based techniques. Access to the heart is usually through a small incision and the procedure may be performed without stopping the heart and using the heart-lung machine. A plug is delivered to close the VSD via a catheter placed through the small hole that the surgeon created. Recovery from this procedure is quicker than with standard surgery.

Surgery to close a ventricular septal defect generally has excellent long-term results.

Giselle's Procedure

Giselle was admitted to UCSF Children's hospital on Monday for her surgery. The surgery was performed that afternoon and lasted for about three hours, though the actual act of patching the hole in her septum only lasted for about an hour. The rest of that time was spent monitoring her condition in the operating room in case more work was necessary. The surgeon who perfomed the operation met us in the waiting room to inform us that the operation was a complete success. There were no complications and they were able to patch the hole entirely.

Next, Giselle was taken to the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Here, she remained under the care of highly skilled nurses and doctors for the next three days. They constantly monitored her progress and ensured that she healed properly. Chest X-rays and echocardiograms were taken periodically to monitor the internal condition of her heart. She also received respiratory therapy to eliminate fluid accumulation in her lungs. On Wednesday, the doctors removed tubes that had been inserted into her chest cavity to drain fluid around the surgery site. All of these procedures were extremely effective, and on Thursday morning she was moved out of the ICU to the transition wing, indicating that her condition was stable and she would be discharged before too long.

On Friday morning the doctors informed us that Giselle was well enough to go home! She was discharged early that afternoon and has been home since. In the hospital she was clearly in discomfort following the surgery. She was given morphine to help with the pain. This was later reduced to Tylenol, then nothing, as the pain diminished. She was pretty cranky in the ICU, uncomfortable and constantly being examined by various medical professionals. By Wednesday of her stay she began to feel much better, and started to smile at her nurses. On Thursday she was playing with toys and acting almost normal, though still clearly somewhat uncomfortable. Over the weekend after returning home, she stopped taking Tylenol and began to act like herself, smiling, laughing and rolling around. Her appetite also came back strong, and now she is eating far more than she did before the surgery. With her heart repaired she is showing many signs of improved energy now that more oxygenated blood is coursing through her little body. A week after the surgery, one would not know that anything had happened to her, if not for the scar running the length of her breastbone!

Next, Giselle was taken to the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Here, she remained under the care of highly skilled nurses and doctors for the next three days. They constantly monitored her progress and ensured that she healed properly. Chest X-rays and echocardiograms were taken periodically to monitor the internal condition of her heart. She also received respiratory therapy to eliminate fluid accumulation in her lungs. On Wednesday, the doctors removed tubes that had been inserted into her chest cavity to drain fluid around the surgery site. All of these procedures were extremely effective, and on Thursday morning she was moved out of the ICU to the transition wing, indicating that her condition was stable and she would be discharged before too long.

On Friday morning the doctors informed us that Giselle was well enough to go home! She was discharged early that afternoon and has been home since. In the hospital she was clearly in discomfort following the surgery. She was given morphine to help with the pain. This was later reduced to Tylenol, then nothing, as the pain diminished. She was pretty cranky in the ICU, uncomfortable and constantly being examined by various medical professionals. By Wednesday of her stay she began to feel much better, and started to smile at her nurses. On Thursday she was playing with toys and acting almost normal, though still clearly somewhat uncomfortable. Over the weekend after returning home, she stopped taking Tylenol and began to act like herself, smiling, laughing and rolling around. Her appetite also came back strong, and now she is eating far more than she did before the surgery. With her heart repaired she is showing many signs of improved energy now that more oxygenated blood is coursing through her little body. A week after the surgery, one would not know that anything had happened to her, if not for the scar running the length of her breastbone!